Synopsis

and they say (240 pages) is a very popular book by Susana Sanches Arins about the reality and consequences of the Spanish Civil War. It has a second revised and enlarged edition dating to 2019 and was awarded the Narrative Prize at the Fifth Galician Book Gala in 2020. It is unusual in that the book is not made up of chapters, but of short fragments separated by blank lines. Also, the author does not use capital letters, so names are given lower case and there is no capital letter at the beginning of each sentence.

Truth is in the stories we tell each other, according to a quote by Luandino Vieira that opens the book. It is also in what is left unsaid, in silence and understatement. The book takes the form of a family saga. We gradually learn about the different family members, who played different roles in the Spanish Civil War, but we learn not from facts so much as what we hear about them. A particularly emphatic role is given to the ‘chorus’, as in a Greek tragedy, where the chorus comments on events and provides some sort of closure.

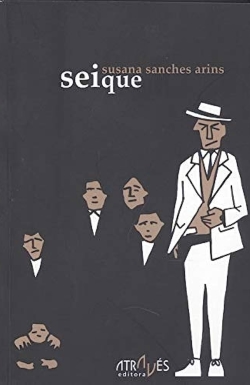

In the first fragment, we learn that ‘stories are always being constructed’. The narrator’s parents were born after the Civil War ended, in 1949 and 1952, but the war is always there. The narrator hears stories from Grandma Glória or from Aunt Ubaldina by the mouth of her daughter, Casilda. The narrator comes ‘from a family built on longing’, that used to have a big house in Portaris. The only family photograph kept by her grandmother shows her grandmother’s family, in which the prominent figure is her grandmother’s older brother, Uncle Manuel, who is dressed in a white suit. The others look like servants next to him. Every week, there would be at least two priests sitting at the table for lunch. The property had one field for every day of the year and at least thirty tenant farmers. Memories are slippery like fish, it is difficult to pin them down. Uncle Manuel is permanently ill, Grandma Glória remarks at lunchtime, he might not make it past Christmas, but he never actually dies. He may have become mean because of a failed relationship.

The narrator relates a case of resistance by the peasant farmers, who in 1915 refused to sell their produce in town because they were required to pay more taxes than the large landowners. ‘lives are lives when they’re mentioned and talked about and noted […] and that’s why memory is important. it provides a space for names and faces.’ But there are those who ‘didn’t want to have a life, they didn’t want to be remembered’. We write about them ‘because they don’t deserve to be anonymous […] their lives were the suffering of others’. The narrator feels sorry for the oxen hauling carts laden with produce. Only the two youngest children were born in Portaris: Grandma Glória, and Aunt Ubaldina, whom the narrator’s father loved like a mother. Aunt Ubaldina was also famous for having a garden with cucumbers.

Uncle Manuel managed to diddle his brothers and sisters out of their inheritance. Only two sisters succeeded in collecting their share: Aunt Carmem, who was a nun, and Aunt Ubaldina, whose husband, Uncle José, stood up for her and got the better of Uncle Manuel. The chorus then comments ‘if that’s how badly he treated his sisters and brothers, imagine how he treated people who weren’t his family…’ Uncle Manuel was mayor of his town for a few years. The narrator imagines Uncle Manuel maltreating his father as he dragged the plough over his fields. In her mind, the suffering endured by the oxen and her great-grandfather are one and the same. The narrator’s father reminds her that in the family photograph Uncle Manuel was dressed in a dark suit, not a white suit. This is the eel of memory slipping through her fingers.

It was Grandma Glória who looked after her father when he was dying. That was why the narrator’s father and his brothers and sisters spent so much time at Aunt Ubaldina’s house in Lois. Before the Civil War broke out, there were meetings to discuss agrarian issues. An agronomist, Cruz Gallástegui, experimented with hybrid corn and crossed types of livestock to improve their productivity. He also founded a union of seed producers. Uncle Manuel’s son was so appalled by his father’s treatment of his mother that he fled to Argentina and never returned. The six surviving brothers and sisters laughed at Uncle Manuel’s funeral when the priest praised his good life and Christian spirit, but at least his death had brought them together.

In an aside, the narrator writes, ‘trees have an advantage over us. they don’t have a voice, and because they don’t have a voice, storytelling doesn’t happen with them. and when there’s no storytelling, there go memory and history, which are pretty much the same thing […] that’s why trees live so long. they live through generations we can’t even imagine simply because they’re not dragging along the baggage that shortens our lives.’ Both the narrator’s grandfather and Uncle José loved trees because they represented a future investment. Shade and fruit were just the short-term benefits. Grandpa Ramiro planted a walnut tree for the narrator and her sisters so they would be able to eat walnuts, to teach them sustainability. Meanwhile, Uncle Manuel got so into debt the big house in Portaris was repossessed and the land turned back into a forest.

The narrator had an uncle called Pepe who emigrated to Madrid and had a chain of hardware stores, from which he made a lot of money. He was the spitting image of Uncle Manuel, and the narrator didn’t like him, because he used to feed his pet dog sirloin steaks while the children had to gnaw away at spare ribs. Uncle Pepe fled to Madrid to get away from Uncle Manuel and his cruelty. Atrocities come about because of the way the system is organized, and also because it brings out the bad in people. The narrator writes despite the private pain she might cause her relatives because of Uncle Manuel and his unnamed perversity. She continues to write in the hope that it will encourage other voices to speak. Grandpa Ramiro was labelled a thief by Uncle Manuel and the local priest and went to prison when in fact it was they who had broken into a lady’s house and stolen things. Uncle Manuel prevented the stonecutter from providing stone for Aunt Ubaldina’s house by threatening him with a pistol. Uncle Ramom was also a Falangist, but he was one of the good ones. Grandma Glória had a difficult time surviving with her husband in prison and opened a tavern to make ends meet.

The problem the narrator has is that she has no documents to prove all the bad things that Uncle Manuel did. ‘without papers to prove it, and without voices to speak, what story can i hope to tell?’ she wonders. Uncle Rafael abducted his wife, Encarna, because her father, the local doctor, refused to let her go with a Falangist. He shot him in the leg and was later arrested. Uncle Manuel put Aunt Ubaldina on the list of poor people who qualified for charity in order to hurt her. In retaliation, Aunt Ubaldina went to claim the basket of free produce as a way of showing how pitiful Uncle Manuel was. There are three stages to the trauma of war according to the psychologist Anna Miñarro: for the first generation, war is incomprehensible, they can’t understand how it could happen; for the second, it is the thing that should not be mentioned; and for the third, it is the unthinkable, something that couldn’t have happened in their family. The narrator just wants to break the chain of transmission.

Uncle Rafael and Aunt Encarna fought a lot. Aunt Encarna accused Uncle Manuel of being an assassin. In 1943, a local woman, Cintia, travelled to the place where her son had been shot and had a photograph taken of her embracing the tree against which he had been killed. When Grandpa Ramiro was imprisoned, Uncle Manuel offered to buy the lands that belonged to Grandma Glória as a way of helping her. He got the lands, but may not have paid anything. Grandpa Ramiro was forced to pay back 885 pesetas for the theft he never committed. This debt tied Grandma Glória to Uncle Manuel and forced her to pay him visits. At the same time as Grandpa Ramiro went to prison for 885 pesetas, Uncle Manuel paid 5,323 pesetas for three piglets – ‘freedom wasn’t worth even what a pig was.’ As a result of the debt, Grandma Glória’s assets were frozen and her children were taken away from her.

The repressive violence of 1936 was used as an excuse to settle personal vendettas. Uncle Ramom, the ‘good falangist’, managed to save a few people by warning them that Uncle Manuel was coming to get them. At a banquet in Portaris, Uncle Manuel once received a package. Thinking it was a present to make up for someone’s absence, he opened it only to find two shrivelled tomatoes and a note telling him to ‘go die in korea’. At a presentation of her book, the author is approached by Célia, Uncle Ramom’s daughter, who says her father was good and saved a lot of people. History is written by the victors, but it’s also unwritten. That’s why Uncle Manuel only appears as the mayor of his town for a few years, not as an assassin. The narrator has her suspicions that Grandpa Ramiro went to prison not because of the theft, but because of his ideological beliefs. Uncle Manuel was sentenced to a year in prison for killing a tavern owner in Ribadumia. He was later cleared because the priest spoke up in his defence and there didn’t appear to be a motive.

An artist, Manuel Pesqueira Salgado, enlisted in the Legion in order to save his life. While there, a bomb exploded in his hands. His right arm, the artist’s arm, was useless and he had to paint the rest of his life with his left. A peasant, Manuel Barros Torres, refused to pay excise tax on goods, a tax the large landowners were exempt from, so the Falangists came around and gave him and his wife a beating. Meanwhile, there were landowners so rich they could afford to bet a house on a game of cards. A guerrilla fighter from Chaira, Carmen Rodríguez, was tortured. Her nails never grew again and, whenever something rubbed against her skin or her children hugged her, bruises would appear, a symptom of the psychological wounds she carried. Uncle Manuel is considered the greatest repressor in the area where he lived and even in the twenty-first century informants do not want their names linked to his, they are still so terrified of him.

In autumn 2009, the remains of Ramón Barreiro and Castor Cordal were recovered by the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory and returned to their families. Josefa Cordal had been nine when her brother was killed. She recovered his remains when she was eighty-three and called it the happiest day of her life. A Republican, Santiago Otero Pouso, was dumped at sea. When his body washed up on a beach, people ran to inform his family, so they could bury him. To stop this happening, the Falangists tied stones to him (or stuffed him with stones, according to another version of the story) and dumped him at sea a second time. They say the person who did this walked without a shadow, because even his shadow didn’t care for him. At presentations of her book, the author meets lots of people who want to share their stories. As a teacher, the author, Uncle Manuel’s great-niece, came into contact with the great-nephew of someone who had been assassinated, but they didn’t want revenge, they understood they were not responsible for their ancestors’ actions, and at this point the author realized they could talk about this history.

One girl, Pilar, was raped by eighteen Falangists, but still didn’t give her father, who was hidden in the house, away. Ramón Barreiro’s mother didn’t give him away, either, despite having her hair shorn, being raped and blinded with acid. She gave up her life rather than betraying him. When Ramón was eventually ‘taken for a walk’, the Falangists cut off his finger in order to get his ring, and that was how they recognized his body when it was later recovered. When Josefa Cordal’s brother was killed, Josefa was expelled from school for being a ‘rotten apple’; Josefa’s sisters were made to dance naked. When the author finished her book, she gave it to her father to read and offered to change the names, so people wouldn’t be able to associate them with their family, but her father said no, that way Uncle Manuel would continue to be anonymous and would win the war again.

In this startling book that relates to her own family, Susana Sanches Arins revisits the horrors of the Spanish Civil War and the repressions that followed, in which her great-uncle, Uncle Manuel, played a key role. And yet Uncle Manuel only appears in the history books as mayor of his town for a few years. By telling the stories, by allowing the voices to speak, even though some of these memories have to do with her own family and paint them in a bad light, the author hopes to bring healing, to break the chain of transmission. Her aim seems to be justified when one of her own pupils is willing to talk about the history, despite the fact his great-uncle was murdered by the author’s great-uncle. Emphasis is given to the horrors of those years by constant repetition and by the way the chorus remarks on the events, and a certain oral tradition is incorporated into the narrative by the way the author describes people’s reactions when the first edition of her book was presented. This is an essential read for anyone interested in the history of that period.

Synopsis © Jonathan Dunne