Sample

I

I said to my father one day:

‘Your ear is red.’

And he replied:

‘Paulo, stop talking nonsense. Instead of a ten-year-old boy, you sound like a ten-month-old baby!’

What a smarty-pants, my dad. What a joker. What nice things he has to say.

I told him this because he spends the whole time talking on the mobile. There are times I stop playing or watching TV just to count the minutes he’s able to talk non-stop on the mobile. Believe me, he’s a phenomenon, one of a kind. His record is twenty-three minutes (minutes, mind, not seconds). That was when he received a call from the office at some unearthly hour (my mother was in bed, Grandpa and me too, we all got really annoyed because he wouldn’t shut up and there was no way we could sleep with him talking on the mobile, especially when he started shouting like crazy, ‘That’s impossible! The budgets have been in since September. I want that on my desk first thing in the morning!’ Work stuff, right?). That time he talked non-stop for twenty-three minutes plus a few seconds. But seconds don’t count, not for the record. Just minutes. Twenty-three. Though if we were to add up all the time he spends chatting away on the mobile from dawn to dusk, there’d be a lot more minutes than that. Way more. An unbelievable amount.

If talking on the mobile was an Olympic sport, my dad would take gold, you can be sure of that.

Which is why I told him his ear was red. Anyway it was true, I wasn’t making it up. His ear was as red as the tomato sauce Mum throws on top of the spaghetti. Bright red from all that talking on the mobile. Red and cooked like a velvet swimming crab.

Yummy.

Another day, it was funny, I hid his mobile. To see what would happen. He’d gone into the bathroom to do those things one does in the bathroom and left his mobile on the sitting room table. It was an unusual situation because normally he’d take it with him into the bathroom. In fact he has it with him all the time, hanging on a coloured band with the name of his company on it, some kind of elastic necklace (you know, I even think he sleeps with it, puts on his pyjamas and gets into bed with his mobile hanging around his neck, just in case he receives a call at night). So, as soon as he’d gone into the bathroom, I took it and hid it under my bed. You wouldn’t believe the state he got into, just because his mobile had disappeared. He rummaged around inside his jacket. He searched the house from top to bottom. He even went so far as to blame my mother for having lost it.

Poor thing.

She said Dad needed to see a shrink.

I don’t know what that means.

But he sure does.

In the end he found out it was me because the mobile started ringing. So he saw where the sound of the call was coming from, the mobile turned up and he knew who’d been playing tricks.

‘You’re just like your grandfather!’ he shouted, all worked up, while grabbing the phone to answer it. ‘All day long, just like him, playing tricks. You’re as bad as each other.’

Grandpa, who up until that point had remained silent, watching with some amusement my dad’s despair in search of the lost mobile (now that would make a good title for a film, Dad in Search of the Lost Mobile, like Indiana Jones or something), turned serious and replied:

‘I don’t play tricks! My brother Bernardino never told me I played tricks. Everything I do, Bernardino thinks is quite normal.’

Grandpa, only he knows why, refers to his brother Bernardino at every opportunity. Bernardino did this or Bernardino said that or Bernardino thinks this or the other… Bernardino, whatever.

I asked Dad a long time ago about Uncle Bernardino (if he’s Grandpa’s brother, that makes him Dad’s uncle and my great-uncle). But Dad turned all serious and said:

‘Uncle Bernardino doesn’t exist. Don’t pay your grandpa any attention. He only ever talks nonsense.’

Dad never stops looking at his mobile, as if he thought it was going to escape or something, like, you know, sprout legs and run around the corner. He sits down to watch telly, leaves his mobile switched on on the glass table and keeps picking it up to see if he’s got any messages or a call. I say to him:

‘But, Dad, the mobile didn’t even go off. Stop picking it up all the time. You’re like a child with a toy.’

He doesn’t answer, but gives me that look he uses when he wants me to be quiet. According to him, I’m only ten years old and what do I understand?

I suppose that’s true, I don’t understand grown-up stuff.

I don’t understand, for example, how my dad can work at the office until eight every day and yet, when he comes home, those bores from the office keep on ringing him. It appears his fellow workers don’t know how to function without him. When I’m at school, I finish classes and head out the door, the teacher doesn’t then call me at home to give me further homework (thank God!). But Dad gets calls. That’s why he only ever thinks about work.

My mother said to him the other day:

‘All you ever do is work. You could turn off that device when you get home. Couldn’t you do without that thingy from time to time?’

‘You know full well I can’t do without that “thingy”, as you call it,’ he replied very seriously. ‘Business is going well. We’re earning lots of money at work and, if I carry on like this, the boss will just have to promote me. So what I have to do is work hard so I can make progress.’

‘Bernardino doesn’t have a mobile phone!’ shouted Grandpa from bed.

And just when my mother was going to tell them both where to get off (my father because he won’t switch off his mobile phone, my grandfather because he keeps on talking about Bernardino, who doesn’t exist), the mobile went off (saved by the bell!), my father pressed it against his ear, stood up and started pacing up and down the hallway, dealing with work things. By which I mean, making his ear go red. He almost beat his record that day.

He was only a minute off.

So, you see, my father never forgets his mobile phone. He may forget me (there are days he doesn’t even look in my direction) or Grandpa (the same), but not his mobile.

My father really works his socks off.

II

As I was saying, my father sometimes forgets I even exist. Or Mum and Grandpa exist. For my dad, it’s often just a case of work.

But Grandpa forgets about things. Grandpa often repeats things because he’s forgotten he’s already said them. We feign surprise, as if it’s the first time we’ve heard them, even though he’s told us heaps and loads of times, and even a few more. Grandpa forgets everything – there are times he doesn’t even know my dad, even though he’s his son and pretty easy to recognize because he always goes about with a mobile stuck to his ruddy ear. He’s completely forgotten about my mother, there’s no doubt about that. He doesn’t know who she is and sometimes goes so far as to call her ‘madam’.

But the funny thing is the only one he always remembers, always, always, is me.

Well, not exactly.

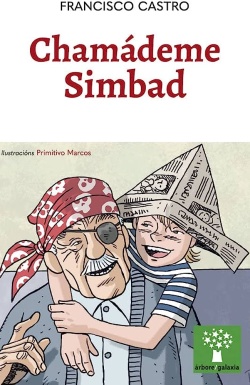

‘Come on, Sinbad!’ He calls me Sinbad even though my real name is Paulo and I’m his grandson (he doesn’t remember that, or he’s forgotten it). ‘Bring your sailing ship over to me.’

So then I pretend I’m getting on an imaginary ship (what I really do is get on the sofa in the sitting room, especially when my mother isn’t looking) and say:

‘Never fear, Captain, I’m coming!’

‘Will you rescue me from the clutches of these filibusters?’

‘I’m almost there! I’ll finish them all off! Hold on!’

And then Grandpa laughs like a little boy.

And stuff happens.

His teeth fall out, for example.

Or he waves his arms about and knocks things over, as if he were locked in a struggle with those people he calls ‘filibusters’. Needless to say, I don’t know who they are because we still haven’t had this explained to us at school.

They must be some kind of bug in Natural Sciences or something like that.

In short, when Grandpa and I fall to playing, stuff happens.

Disaster strikes.

And when disaster strikes, my father comes and tells me not to bother Grandpa, not to ‘inflame his feelings’ (this is one of his favourite phrases, as if I was going to attack Grandpa with a flame-thrower and scorch his head or something) and to go and play with some children my own age.

That’s right. Perhaps I should do that. Play with some children my own age.

The thing is hardly any of the ten-year-olds I know are half as much fun as Grandpa.

I asked him, ages ago, when I was smaller:

‘Why are you such fun, Grandpa? Why do we have such a good time together?’

Grandpa set me on his knees and replied:

‘Because you’re Sinbad the Sailor and I’m the Captain of the Seven Seas! You, Bernardino and I are inseparable. We’re the boldest, bravest pirates on the open sea.’

As I say, I was small at the time, but I wasn’t stupid and I knew this wasn’t the right answer.

‘No, really, you’re not like other people’s grandpas. You don’t behave the same or do the same things.’

He turned very serious when I said this. His eyes glassed over, and I thought he was going to burst into tears.

I got frightened.

He fell silent and then, after a minute or two, came out with this reply:

‘There are times my head goes wobbly and I can’t remember things, I get all confused and my memories get all mixed up. That’s why the doctors want me to take these pills and your father takes me to see them so they can do tests and stuff like that.’

Having said this, Grandpa placed me gently on the floor and stood up to look out of the window. He was very serious. He was looking outside, but I knew he had his eyes on another, distant place.

I asked him:

‘What are you looking at, Grandpa?’

‘Bernardino’s house.’

Not knowing quite what to think, I went outside to play. I didn’t really feel like it. As I was going down in the lift, still thinking about Grandpa’s sad, serious face, I remembered my parents saying something about Alzheimer’s the day before. It was something like that. It struck me as an ugly word and – don’t ask me why – made me feel afraid to hear it, that Grandpa could be suffering from something like that, could be ill as a result of Alzheimer’s. I really didn’t know what they were talking about. But what followed, which I shall now tell you about, helped me to understand it.

III

Grandpa doesn’t always play with me.

That happens when he has his ‘periods’.

That’s what my father called them. After Grandpa fell sick, he said from time to time he would have ‘periods’. ‘Tricky periods,’ my father called them. What Grandpa had was just beginning; later, it would get worse and his illness would pass through different ‘periods’. That’s what he said. He sometimes says ‘periods’. Other times, he says ‘phases’.

To start with, I didn’t really understand all this business about ‘periods’ and ‘phases’. Later on, I still didn’t understand. Now I think these ‘periods’ are when Grandpa isn’t himself, I don’t exist as Sinbad or anybody else, none of my family exists because he doesn’t know us, and Grandpa knocks stuff over because he feels like it, or refuses to get in or out of bed.

Those days that drive my mother crazy.

That’s what she says, the old man is driving her crazy, she can’t endure the old man, she’s had enough of the old man. I don’t like it when she calls him ‘the old man’. I prefer it when she calls him ‘Grandpa’ or ‘your dad’, as she does in front of my dad when they’re discussing Grandpa’s ‘periods’.

Grandpa sometimes spends hours sitting on the sofa, in front of the telly when it’s turned off, and doesn’t want to eat or drink or get up or anything. My mother says he’s driving her crazy. Other times, he decides to do the opposite and won’t stop wandering around the house. And, of course, this drives my mother crazy again. When he’s in one of his ‘periods’, he’ll get up at some ungodly hour, when we’re all asleep. It’s like he waits until we’re asleep before getting out of bed.

One night, he got up at some unearthly hour and whacked the television on at full volume. My father leapt out of bed and shouted to him to turn it down. Grandpa said Bernardino always let him watch the television whenever he felt like it. My mother reiterated that the old man and Bernardino were going to drive her crazy. And all I could think of doing was sitting down on the sofa, as if I was going to watch television with him.

I sat down next to Grandpa and asked him:

‘What’s up, Captain?’

He didn’t reply. My father almost dragged him off back to bed and said, if he refused to obey him or pay him attention, then they would have to tie him up. My mother told me off for being out of bed at such an ungodly hour.

‘Into bed with you, Paulo! What on earth are you doing here, are you dumb or what?’

I didn’t reply. I was there for the same reason as everybody else. Grandpa had been up to his tricks again. As when he emptied the fridge and scattered the contents all over the kitchen floor. Or started shouting at his reflection in the mirror.

‘It’s because of the Alzheimer’s, right?’

‘Yes,’ said my father while taking my hand so I would go back to bed, ‘it’s because of that damned Alzheimer’s.’

‘Is that why he talks about Bernardino his brother?’

‘That’s right. Now come on, you, get into bed and stop being a nuisance. I have to work tomorrow and I’m not going to get anything done unless I sleep a little.’

Dad put me into bed and, even though it was five in the morning or something like that, he still took a peek at his mobile to see if anybody was ringing him…

This man, I thought, he’s a lost cause.

The day after the incident with the television, being so frightened on account of what had happened (I didn’t get back to sleep after that and had real problems getting anything done at school), I asked my father what this Alzheimer’s was all about.

‘It’s an old people’s disease.’

‘What do you mean, old? When we all get old, are we all going to do the same strange things as Grandpa does?’

‘No,’ replied my father while wolfing down his morning toast at top speed (he always has breakfast at top speed, lunch at top speed, dinner at top speed, with his mobile on, as you can imagine, my father does everything at top speed, by which I mean attopspeed). ‘Not all old people get this illness. Your grandfather happened to get it, it means his head doesn’t work properly.’

‘You mean he’s gone crazy?’ I asked this question thinking about my mother.

‘Not exactly.’

I left my breakfast where it was and followed my father to the bathroom. He was brushing his teeth (attopspeed). I asked him:

‘Will he always be like this? Does the illness have a cure?’

My father, while straightening his tie, explained:

‘Listen, Paulo, Alzheimer’s means his head doesn’t work properly. People suffering from this disease sometimes don’t remember things or behave strangely. If you see your grandpa doing funny things, then that’s the reason.’

‘Do they turn into children?’ I asked him from the door as he headed towards the lift, gazing attentively at his mobile.

‘Yes, sometimes they do, like children. Now shut that door because I’m going to be late and I have to make a call.’

My father disappeared.

His ear was red, and he still hadn’t explained anything.

Attopspeed.

IV

Despite the speed with which he gave it to me, my father’s brief explanation helped me to clarify a few things. For example, why he called me Sinbad instead of Paulo. Because that’s who I was for my grandpa, like that Sinbad in the story Sinbad the Sailor. And when he called me Sinbad, he wanted me to call him Captain, not Grandpa. Or Blond Beard. Or Blue Beard. Or the Captain of the Seven Seas. I searched in an atlas and discovered there are more than seven seas. There are at least ten, or something like that. But he says he’s the Captain of the Seven Seas, and that’s fine by me (who’s the captain of the other three, then?).

Grandpa would turn into Captain when we were alone, on the whole. My mother would have to go out to do some shopping or to run an errand. She doesn’t leave the house very much because she has to look after Grandpa. She doesn’t go out, and this drives her crazy. That’s what she says, as I told you, she’s going to go round the bend (but don’t get the wrong idea about her, I know she loves Grandpa a lot, you only have to see the way she gives him his food, how tenderly and patiently she does it. When Grandpa’s going through one of his ‘periods’, he may not want to eat, he may clamp his mouth shut and say he wants some cakes or sweets, and my mother, very delicately and patiently, will start talking to him slowly so she can put some food in his mouth and that way he’ll get some food down him. The way you do with babies. That’s why Grandpa’s so thin and boasts such a good figure). Mum says she doesn’t want to leave us alone, just in case. I always tell her to go out, it doesn’t matter, I can look after Grandpa perfectly well on my own. But she says no, she won’t, she prefers to stay at home. Sometimes, however, she has no choice but to go out.

And then, when Grandpa and I are left to our own devices, we turn into Sinbad and Captain, or Sinbad and the Captain of the Seven Seas, or Sinbad and Blond Beard or Blue Beard or Any-Other-Kind-of-Colour Beard, depending on where Grandpa’s at or what mood he’s in. And then, I have to say, everything becomes a lot of fun. Grandpa and I play, for example, at hiding things about the house. In the strangest of places (inside the soup pots, on top of the bookshelves, inside the lamps…). ‘They’re treasures!’ exclaims Grandpa. ‘We’ll have to draw a map so we don’t forget where we’ve put them!’ Grandpa then tells me the filibusters – those baddies I couldn’t tell you who they are, but they’re obviously particularly bad – the filibusters, as I was saying, have pinned him down, and so I grab my ship (the other chair), sail to his island, rowing across the sitting room (dragging my bottom across the floor) and rescue him.

‘Careful, Sinbad! There, on your right!’ shouts Grandpa.

And so I stab with my sword and give a shout as if I’d just hit one of the baddies.

And Grandpa, from his chair, because he can’t move a lot, cries out:

‘Sinbad, the filibusters have got me!’

And I go and give a wonderful leap (jumping from chair to chair like Spiderman through the air… as I said, I only do this sort of stuff when Mum isn’t around, because otherwise…) and set him free. And we have the time of our lives.

That was until one day in February.

One gloomy Sunday when we all got up to have breakfast and found Grandpa wasn’t with us anymore.

V

None of us knows exactly what happened.

Mum told the police she hadn’t heard a thing, and that’s strange because my mother sleeps very lightly, so much so that, if I cough or dream out loud or anything else happens in the night, she quickly gets up and comes to my bed to see what’s going on. She has this kind of radar that detects every kind of nocturnal sound, she doesn’t miss a single one (well, she did manage to miss the sound my grandfather must have made when he left the house… that’s a shame, her radar let her down). My father told the police the same thing, more or less, he hadn’t noticed anything (now if Grandpa, before leaving, had happened to call him on his mobile, then he would have realized what was going on…). As for me, to tell the truth, I couldn’t tell them anything because I usually sleep like a log, I’m out for the count, when I close my eyes, there could be an earthquake or a nuclear explosion inside the house, I still wouldn’t wake up.

When the police left, my parents went out again in a state of nervousness to search the local area, as they’d done when we’d got up and seen Grandpa wasn’t there. The neighbours helped to see if we could find him between the lot of us. He couldn’t have gone very far, we were sure he’d turn up at any moment. Apart from that, he has difficulty moving about. I was left with María, who’s my best friend. She’s also my neighbour. She lives in the flat downstairs and is in the same class as me. We played a whole bunch of stuff that Sunday morning. What I wanted was to go out looking for my grandfather, but they wouldn’t let me. It seems I’m not big enough to go wandering the streets on my own, let alone to go searching for a missing person. I asked my father to take me along, I wouldn’t budge an inch from him, just take me, I couldn’t stand the tension and wanted to do something, just take me along, I couldn’t just hang out in María’s house as if nothing untoward was going on, just take me, Dad, please, please, I kept on insisting, take me with you to go looking for Grandpa. But my dad wouldn’t listen, he shouted at me and told me to go to María’s. I suppose he was very anxious because of what had happened that morning, and that must have been the reason he shouted at me so rudely. So I left for María’s and played a whole bunch of stuff with her. I think María made a real effort that day to ensure I was having fun, to keep my mind occupied with a hundred games, so I wouldn’t think about Grandpa, where he was, what can have happened. Her mother made some spaghetti and, after lunch, we watched a film. I tried to hide the fact I was worried. But I really was. And I felt like crying. Like bawling my eyes out.

But I held on. I didn’t want anybody knowing how sad I was.

Because pirates don’t cry.

In the evening, my mother came to fetch me and, back at home, my father explained that Grandpa had left while we were sleeping and, because of that business of Alzheimer’s, he must have gone for a walk and then not known how to get back, that happens a lot, people suffering from that disease forget the way home, they get disoriented, and then they get frightened and can’t find the way home. But I wasn’t to worry. He would soon turn up, the police were on the case, and probably the next morning they would tell us something, the best thing now was to get some sleep, it was way past my bedtime, there were lots of people looking out for him, all the police officers in the city, he told me, had been informed, as soon as somebody found something, they would give us a call.

I listened to him, but didn’t say a word.

Mum put me to bed.

She tucked me up.

When she turned out the light, I burst into tears. Nobody heard me, but I cried my eyes out.

I went to sleep feeling very sad, unable to work out why my Captain had left like that.

VI

As I told you, Grandpa left home one Sunday in February. It was just two weeks before Carnival, one of the times in the year I like best because there’s no school (that’s the main reason) and because of the costumes and parties (another good reason). On this occasion, however, I wasn’t much in the mood to get dressed up and go outside to have fun and do things (even though I like Carnival a lot more than Christmas; that said, you get a lot more days’ holiday at Christmas… so I’m not so sure…). I’d decided on my costume a long time before. I was going to go as – can you guess? – Sinbad the Sailor! Who else? Grandpa had given me all the important details before leaving home, had explained everything there is to know about getting dressed up as Sinbad the Sailor. He told me I would have to wear a turban on my head and carry a large, curved sword on my waist, a sword that is known as a scimitar (what a crazy name for a sword…). Mum had bought me the whole outfit in a shop and had laid it all out on top of my bed. All I had to do was put on the disguise, and I would go back to being Sinbad the Sailor.

‘Come on, Paulo, let’s go out. Put on the outfit.’

‘I don’t feel like it, Mum.’

Mum looked at me for a moment and then went to the kitchen. I heard her telling my dad that he needed to talk to me, I had been a bit strange ever since Grandpa had disappeared. Well, would you believe it? Who wouldn’t be a bit strange if their grandpa had disappeared? That was the least of it. I couldn’t understand a thing. I couldn’t fathom out how it was possible for the police not to have found my grandpa. It couldn’t be that difficult. A half-bald old man with white hair and checked slippers. There couldn’t be that many out in the streets!

My father came to see me in my bedroom.

‘Paulo, you need to get dressed up. It’s Carnival. Don’t you feel like it?’

I didn’t reply.

My father sat down next to me on the bed. He repeated the same stuff he’d been saying to me for days over the last two weeks: it was just a question of time before Grandpa turned up, Grandpa’s illness was like that, sometimes he was OK, other times he wasn’t, he was sure he was safe and well, any moment now we’d receive a call asking us to go and fetch him… All I had to do was be patient, like him.

‘But why haven’t they found him yet?’

My father fell silent because he didn’t know how to answer that question. His mobile went off a moment later, but he switched it off.

‘You’ll see how Grandpa will turn up any day now,’ he said again.

He stood up to leave and was just about to go through the door when I asked him another question (I still don’t know why I did this):

‘Did Grandpa tell you the story of Sinbad when you were little?’

My father stopped short, staring at his mobile, as if his mobile had asked him the question and not me. I could see his look of surprise. He hadn’t been expecting this question.

‘You what?’

I knew he’d heard me, he wasn’t deaf. So I kept silent. In the end, he answered, he didn’t have much choice.

‘Yes,’ he sat back down beside me, ‘Grandpa told me the story of Sinbad the Sailor many times. He told it to me many times. He even had this fat book with the story in it.’

‘What was it like?’

‘The book? Well, it was this old book he’d had for years and…’

‘No. The story. What was the story about?’ I interrupted him.

My father started getting nervous, but I couldn’t tell why. Perhaps it was because he was remembering Grandpa, or it could have been for some other reason. He always had lots of things churning around inside his head, so who knows what he was thinking about when I talked to him? Perhaps he was in a hurry for something, or felt anxious, or there was something else, and so he said:

‘You know the story of Sinbad the Sailor very well. You know it off by heart, so I don’t know why you want me to tell it to you now. Why am I going to tell you a story Grandpa has told you already? He must have told it to you a thousand times, just as he did to me when I was your age, he liked that story so much… So, you see…’

‘Yes, but tell it to me again,’ I interrupted him once more.

He glanced back at his mobile and, having pulled a face as if to say, ‘OK then, you’re a real bore, you know that, let’s see if by telling you the story I can keep you quiet,’ he started telling me the story of Sinbad.

There was once a boy called Sinbad, who was very poor. He met this rich man, and every day Sinbad would go to the rich man’s house, and the rich man would tell him a story of his adventures and then give Sinbad some gold coins, after which he left. This went on for many days. The old man had travelled far and wide across the sea and had lots of adventures.

My father had just got to this part of the story when his phone went off. I used this opportunity to ask him:

‘What was the name of the city where the story of Sinbad the Sailor is set?’

My father hung up the mobile, meaning he didn’t answer this second call either.

‘What was that?’

‘In which city is the story set?’

My father made as if he was scouring his memory for the name of the city. He fixed his eyes on the ceiling, as if the answer might be written up there or something.

‘It was in Constantinople.’

‘No, it wasn’t!’ I said. ‘It was in Baghdad.’

My father stared at me as if to say, ‘So, what does that matter?’

‘Do you want me to carry on telling you the story or not?’ he asked, glancing back at the screen of his mobile. ‘If you’re going to keep on interrupting me, then it would be better if I didn’t tell you the story, I’m just wasting my time.’

I asked him to continue.

Sinbad the Sailor lived in Baghdad (he said this now because I’d reminded him, otherwise…) and, having listened to this old man’s stories (the mobile went off again, he switched it off), he also became rich after coming across a magic lantern in which there lived a genie who (the mobile went off again, he switched it off)… a genie, as I was saying, in the magic lamp there was a genie (Dad was finding it difficult to concentrate, the mobile just kept on going off, as if it wasn’t going to stop), a genie who said he would give him three wishes if he would take him out of the lamp.

‘OK, just a moment,’ I interrupted him again, adopting an expression of patience, the same one our teacher uses in class when she asks us a question and we don’t know the answer because, as she says, we don’t bother to study, ‘concentrate, Dad, concentrate. The story’s not like that. You’re forgetting a whole bunch of stuff. Thousands of tiny details.’

His mobile went off again. This mobile had a mind of its own. My father was getting more and more nervous, unsure whether to pay attention to me or the mobile. The same thing happens to me when I’m in class and Moncho and Martiño try to make me laugh, I want to pay attention to them and the teacher at one and the same time, I don’t know where to look and can’t work out what the teacher is saying, and I always end up getting into trouble. By the way, it’s me who gets into trouble, not them!

‘It is like that!’ said my father, raising his voice a little. ‘The story’s just as I’m telling it to you.’

The mobile went off again. This time, he answered. He told whoever it was (somebody from the office, as always, they don’t know how to live without him) to wait.

‘The story you’re telling me is something else, it’s not Sinbad the Sailor. There aren’t any genies or lamps or anything like that in the story about Sinbad. You’ve seen the rest in a film and now you’re telling it to me because you don’t remember how the story goes.’

‘Would you wait just one moment, please, I’m discussing something with my son? I’ll be with you in a minute. Or better still, I’ll ring you back,’ he said.

‘You don’t remember! You don’t remember!’ I repeated in case he hadn’t heard me.

He hung up and gazed at me severely.

‘Let’s see now, are you going to tell me what the story of Sinbad is all about? Me, who heard it from my father dozens of times before you ever did?’

He was shouting by now.

‘It’s not the way you tell it!’ I replied. ‘It’s completely different. In the story about Sinbad, the REAL story about Sinbad, not the one you keep telling so badly, there was a poor man who carried everybody’s parcels, and that’s why he was called Sinbad the Porter (his mobile went off, and he told whoever it was on the other end of the line to wait; he shouted, “I told you already I’ll call you back! Don’t keep on insisting! Give me a little space! Wait just a moment” And then he came out with this ugly word, which, being a well-educated little boy, I’m not going to repeat, but it was one of those words which, if I came out with it in front of my parents or the teacher, would get me into monumental trouble), and there was an old man who lived surrounded by exotic viands (I remember now whenever Grandpa used this word, “viands” – I still don’t know what it means – he would smile and lick his lips, so “viands” must be something you eat), and old Sinbad the Sailor told Sinbad the Porter the story of his life (my father said he was going to hang up, he couldn’t deal with it right now, he’d call back in a couple of minutes, and he pretended to be paying attention to what I was telling him – the story of Sinbad the Sailor in its correct form – but he kept on fiddling about with his phone, searching for a number or sending a message or something, and I don’t think he was paying me any attention, he was just looking at me and nodding his head, as if to say, “All right, all right, whatever you say, kid, it’s fine by me”), and the old man told how he’d inherited a fortune and lost it several times during his voyages, and then got back all the money only to lose it again, and how he’d lived inside a whale after a shipwreck (my father got up from the bed and started dialling numbers with his thumb), and his men left him on a deserted island again like a castaway (“Listen, I’ll send it to you by email in about five minutes”), and then he was captured by a one-eyed giant (just like Ulysses, my grandfather would add, whoever that may be), and then he escaped and became rich by selling ivory, and…’

He didn’t let me finish the story.

‘Listen, I don’t think you have a clue about the story of Sinbad the Sailor. I’ll tell it to you properly some other day, when I have more time. I have to send something to the office from the computer, I can’t talk to you right now. It’s urgent, you see. We grown-ups can’t spend the whole day playing around or telling stories. We grown-ups have responsibilities.’

(Actually, my father pronounced this last word with great solemnity – re-spon-si-bi-li-ties – emphasizing each syllable by wagging his finger at me, as if this might make the responsibilities sound even more responsible, or he could whack me over the head with them, or something like that…)

‘I do know how the story of Sinbad the Sailor goes!’ I shouted at my father as he got up from the bed, feeling full of rage and very annoyed.

I knew that story very well. I certainly knew it better than he did. How dare he tell me I didn’t know it? It was my grandfather’s favourite story, the one he told me again and again when he was still at home. You should have seen his face whenever he told that story. I knew the story, of course I did! Down to the tiniest detail. It seemed to me my father had completely forgotten it and was annoyed with me for correcting him.

My father doesn’t like being corrected very much…

‘You don’t know it! How can you be so certain you know it?’ asked my father, shouting even more than before. ‘Why does it have to be the way you tell it, and not the way I tell it?’

‘Because Grandpa told me the story a hundred times!’

‘Grandpa’s dumb, understand? Grandpa doesn’t know what’s he doing or what he’s saying half the time! That’s why he left like that, got it?’

I don’t remember what my father said after shouting at me like that. I just remember he went out of the room and I was left feeling very annoyed and sad, on my own there. I suppose he was also suffering on account of what had happened to Grandpa, and that was why he behaved like that and said the things he did.

My father went out of the room. Talking on his mobile. In the direction of the office, where he has his computer. To work a little.

To work a little more…

Don’t ask me why, I know I just said I didn’t want to, but I asked my mother to help me put on Sinbad’s outfit. I wanted to go out into the street and run into all those Captains of the Seven Seas (or Eight, or Nine). I needed to go out, to run around, to laugh and jump. To get some fresh air. I couldn’t explain what was happening to me. I don’t even know why I’d argued with my father like that. The story about Sinbad wasn’t that important, I realize that now. What did it matter if my father couldn’t remember? Perhaps when I’m his age and as big as he is, maybe I won’t remember either. I think, when it came down to it, I argued with my father because I needed to show him I was angry, to express the rage I felt on account of my grandfather, or else because he never has time for me, all day at work, on his mobile, the computer, making calls at all hours, answering everybody… all those things he does so well… Perhaps that was the reason, or I just needed to go out into the street. I would dress up as Sinbad the Sailor, the way my grandfather would have liked. I’m sure if he was still here, he’d be standing by me now, helping me to get the costume ready, giving me advice about how best to play the role of Sinbad. That’s how it would be. But Grandpa wasn’t there. He wasn’t there and perhaps he wouldn’t be there again for a very long while. Or ever again. I thought about that, and yet at the same time I didn’t want to think about it, that was what made me want to get out of the house and leave all those concerns behind. With the costume, it would be as if I could leave myself behind. I’d go out and run into all the filibusters that ever existed. All of them (but then I thought what would a filibuster’s costume look like? How would I recognize them? Would they have legs? Would they have antennas? Were they human? Or animals? Things? Earthlings? Or extraterrestrials?). It didn’t matter. I’d run into all those filibusters. I would know how to recognize them, just as I knew how to do so much, it wasn’t for nothing that the teacher said I was as smart as sixpence. All the filibusters I could find. I felt sad and full of anger. Confused, uncertain whether to burst into tears or laughter.

The days since Grandpa’s departure had been the worst of my life.

I didn’t realize this difficult patch would soon be over and the moment was drawing near when I would embark on the most exciting adventure of my life. Not even Sinbad the Sailor experienced something as fantastical as what happened to me in the days following Carnival, which I shall now tell you all about.

Text © Francisco Castro

Translation © Jonathan Dunne

This title is available to read in English – see the page “YA Novels”.