Sample

1

The important thing is not what you tell, but the way you do it, I always used to say. And that was why I was about to jump over the wall and to desecrate that old cemetery almost everybody had forgotten. Who ever would have said I would end up like this, as a common grave robber? And all because of the nonsense that had got inside my head, that itching sensation that hadn’t left me for an age.

It was a few minutes after seven in the morning, and dawn was just showing itself behind Mount Lobeira, which was stripped of its trees and with its immodest rocks in plain view after so many summers of deliberately started fires. With the dawn, the large iron cross affixed to its summit blazed brightly. Seeing it, I remembered that other cross – the one that is always drawn on pirates’ faded treasure maps in novels and films. It seemed my incessant search lasting all these years was about to end here. I had found it. Finally, I had the chest of gold and jewels within reach. I was a satisfied pirate. A few steps more, and it would be mine. I had succeeded. At last.

Hardly any cars drove along that solitary road at that filibustering hour. Only once in a while the silence would be broken by a bakery delivery van or the late clients of a singles bar further uphill. I had arrived very early and discreetly parked my car in front of Rubiáns municipal cemetery. I had opened the window and lit the first cigarette of the day. There wasn’t a soul in sight. The two sides of the road, which I had taken in Pontevedra, having left the motorway, were full of warehouses and sheds belonging to a wide range of industries on the outskirts of Vilagarcía: repair shops, pharmacy stores, furniture shops and car dealers. Almost at the roundabout at the entrance to town, in Carolinas, was the funeral parlour where I had attended more than one wake. There was also a steakhouse and a couple of bars that were completely shut. The workers of the businesses next to the road wouldn’t arrive for a while in search of the first coffees of the day or the first, anaesthetizing dose of alcohol to insert in their sleepy bodies. The only sign of life was in that club with the flashing red neon where the road began to run straight. It was far away from me, and the fresh breeze brought the echo of a catchy Latino tune that disturbed the early morning calm. I tried to hum along in between inhalations, but choked and coughed loudly.

I still didn’t really know why I was there. Or I did, and I didn’t want to admit it. It was just something I had to do, nothing more. That simple. An impulse despair had given rise to inside me and I had let myself be carried along by. A new command to obey with a fanatic’s blind obedience. Everything else was a sea of doubts, uncertainties and questions. Perhaps I was there because more than a means, I was searching for an end to my novel. Everything had begun here, in this cemetery, and this was where it had to end, closing an enormous circle I had started drawing almost four years earlier. To go back to the origins, the core, the centre. Or else, looking back now, everything had started a whole lot earlier, without me even knowing. Sometimes you had a story inside and didn’t realize. The damn traitor would slowly suck away at you, feeding on everything you read, felt, saw, heard and imagined, everything going on around you. It was like a parasite, a monstrous worm, a leech that grew and grew until you had to throw it out, in case it sucked the very life out of you. That was what had happened to me, and that was why I was there, near the end now, about to vomit it up once and for all. To find the treasure at last, after a sometimes painful process, a sometimes directionless journey I had thought would never end.

I chucked the cigarette butt out of the window and grabbed the bulging folder from the passenger seat. I switched on the reading light and started lazily flicking through the material. It was like coming up against a mirror. I could see myself in every printed sheet, every photocopy, every cutting. Inside was everything I needed, everything I had collected during that period of obsessive work. The spark that had set it all off and put me on the trail: that yellowed newspaper article in which old Edelmiro posed for a photographer while receiving a box with a medal from a smiling man in a uniform. The transcriptions of some of the many interviews he had done – the few that shed a little light on events that had been almost forgotten by some and concealed by others out of a mixture of fear and shame. A sheaf of pages with all the information I had obtained on the Internet, in particular with reference to the Royal Navy’s squadrons in the Atlantic – the Home and Atlantic Fleets – and some of its ships; naval battles from the First World War and German submarines. Dozens and dozens of photocopies of articles from various copies of Galicia Nueva, ‘Vilagarcía’s first daily’, as they liked to call it in those distant years of the last century; old postcards of a town that sadly no longer existed even in the memory of its oldest inhabitants. All the notes from books and articles that talked about Nazi involvement in the Spanish Civil War and Fascist repression in Arousa Bay, which I had borrowed from Vigo Central Library or consulted in the Penzol or Vilagarcía municipal library. And then there was the photo, that print from the family album that showed a past in black and white that had been snatched from me and hidden away. And the most important part of all: the more than 150 sheets with 1.5 line spacing and Garamond font size 12 I had written to date. Remnants of a story lost in the ashen wake of time. A fragmented story I wasn’t sure how to tell and for which I didn’t even have an ending. A story I was uncertain how to take forwards. A story in which my life and the lives of many of its characters were tied up. A story…

I had it all right in front of my nose. I didn’t need any more – certainly not to desecrate a cemetery at the crack of dawn. If I was there, it was because of the whirl of information and history, all those interlinked lives fate had placed in my hands. Because of the mystery they contained, which I hadn’t been able to decipher. Because of everything I had reconstructed, stitch by stitch, like a seamstress, sometimes with the thick thread of truth, others with the thread of supposition, the silken thread of fiction. And also because of shame, that guilty feeling that kept me company. Because of all the deceit, the lies, half-truths, silences, the slab of a consumed and stolen past. Because of all the doors that had closed in my face and I had had to break down. I was there because of Delia, her son, Edelmiro, and all the others… But also because of myself, my grandparents, my mother, my father, my cousin… My family. The past. The present. The future. I owed it to them – they owed it to me.

Slowly, as if afraid they would disintegrate in my fingers, I put all the papers back in the folder, wound up the window, switched off the light and got out of the car. I took a couple of deep breaths, lit another cigarette – the second of the day – and started walking. I left the municipal cemetery and bins full of withered flowers, losses and farewells, behind. I passed in front of a warehouse for repairing lorries, which stank of grease, sulphur and burnt rubber, and took my stand in front of a green gate a little further on, set back from the road. This was my destination, the friendly port that marked my journey’s end. Finally, I had reached my Ithaca.

I looked back at Mount Lobeira. The sky was now completely blue, and the flames lighting it up had gone out as I watched. The large cross was still fixed in the ground, expectant, as if awaiting my decision. The red cross traced on the treasure map I had so longed to lay my hands on. A shiver ran down my spine. I was overwhelmed by emotion, but also by fear, since I didn’t know what would be behind it. I was afraid all there would be in the chest was an anonymous skeleton and I would have no ending for my story. If I couldn’t throw the story out, it would carry on growing inside me until eventually…

I gazed at the wrought-iron gate and the golden letters that said: ‘British Naval Cemetery’. On the stone column to the right, on a small ceramic tile, was the number 62. To the left, painted in black and almost completely faded, the number 16. Above this, a plaque on which was written: ‘Commonwealth War Graves Keyholder – for the keys 43 71 33 Vigo’.

I knew this phone number belonged to the British consulate in Vigo and, if you rang, no one would answer. The consulate had been closed for some time for ‘budgetary reasons’, and Mrs Watford, the consul, had relinquished her diplomatic duties and had yet to be replaced. I had had a pleasant conversation with this woman a couple of months earlier. It had been a brief chat at the door to the consular office on Marqués de Valadares Street. I had bumped into her by chance, as she was turning the key before leaving. She had been in a great hurry, but had still managed to be polite.

‘I’m sorry, I’m in a rush,’ she had apologized.

‘It’ll only take a moment,’ I had replied.

‘It’s just I’m arranging the repatriation of the body of a poor young man from Birmingham.’

‘Was he killed? Here, in Vigo?’ I asked in a state of shock.

‘No, no,’ the charming woman clarified.

‘What happened then?’

‘He was discovered at death’s door, lying in a street on Christmas Eve. Just imagine.’

‘What about his family?’

‘Don’t talk to me about them. Can you believe that, once we’d found them, they refused to take charge of the poor boy’s body?’

‘Really?’

‘That’s right. I understand the boy had run away from home and was living like a tramp, but that’s no reason to be lacking in charity,’ Mrs Watford complained bitterly.

‘We can meet some other day, my business isn’t that urgent,’ I suggested in view of the sad nature of her errand.

‘I’d be grateful. Just give me your number, and I’ll call you.’

She diligently wrote down my name and mobile number in her diary, in a studious girl’s minute handwriting, but never called. The aforementioned ‘budgetary reasons’ got in the way, and we never spoke again.

I went up to the rusty gate. Naively, I tried to push it open, knowing it had been locked by that key Edelmiro had carried in his pocket for so many years. A key he had used on a daily basis. A key that symbolized loyalty to a promise, a refusal to forget the past, gratitude. A key that had saved his life and the life of his family. A key that hid a secret.

I stood on tiptoe and peered inside. I couldn’t see the graves – the hedge was tall and a little unkempt. The lack of Edelmiro’s skilful, careful hands was obvious. I didn’t mind. I knew very well where they were, what the gravestones and crosses were like, even though that was the first time I had been there, so close to them. There were fifteen in all, the vast majority perfectly lined up in a row next to the back wall of the cemetery.

Graves seven to fourteen were occupied by British officers and sailors – there was even a cabin boy, only seventeen years old, by the name of Clifford Seely Slade. They had all been in the Navy and died in the 1920s and 30s. There had been one particularly bitter year – 1921, or to be more exact, the month of January, specifically the 14th to the 27th – when there had been five deaths. Apparently, the cemetery had been consecrated a lot earlier, in 1910, presumably because of the need to bury all those members of the Atlantic Fleet that perished for whatever reason whenever the fleet anchored in the estuary – Arousa Bay, as it was called on maps of the Admiralty – during its habitual stays from the year 1874 onwards.

Graves two to six were occupied by sailors who had passed away in the years 1906, with four deaths, and 1907, with just one – no doubt their remains had been brought here from other cemeteries where they had been buried before, perhaps very near here, in the municipal cemetery of Rubiáns.

As I had discovered during my research, there were more than 2,500 cemeteries like this dotted around the world, scattered in more than a hundred countries, where almost 1,700,000 British soldiers who had met their end in two World Wars had been buried. That said, there were many thousands of civilians buried along with them, whether killed in action or not. The care and adornment of these graves, memorials and gardens were the responsibility of an institution called the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, founded in 1917 by the British general Sir Fabian Ware, who had been a director of the Rio Tinto Company Limited, a company that exploited copper, gold and silver mines in that locality in Huelva, where it was said the first football match in Spain had been played, although others affirmed it had been in Vilagarcía de Arousa. I recalled a few years earlier, in the digital edition of a well-known sports newspaper, there had been a feisty argument about this. All because of an article that referred to a news item published in the issue for 26 June 1873 of the Eco Republicano de Compostela, which talked about the docking in the port of Vilagarcía of an English cargo ship, the Go-Go, with material for the Rio Tinto mines. In their free time, the sailors disembarked in shorts to play with a leather ball, shocking the locals, in what was said to be the first match ever held in the Peninsula of that strange sport played with the feet, which was starting to cause such a commotion in Britain. This documentary reference caused a huge scandal in Huelva, where there were even accusations of falsification and historical manipulation, and lengthy studies by local chroniclers challenging the alleged Galician paternity.

‘And here we are, still looking for bodies in ditches and mass graves!’ I had exclaimed in indignation, when I discovered how the British honoured and cared for their war dead.

I still recalled that article I’d read about a woman – Esperanza, I think her name was – who by sheer determination had managed to exhume, all on her own, the bodies of 150 victims of Fascist repression. With the arrival of democracy, she had spent several years searching for her father and eight other relatives who had been assassinated by Falangists when she was little more than two years old. In the end, it was the selfsame murderer who confessed where her father had been killed, and, using nothing but her own hands and a hoe, she had dug him up along with many others. She had even had to pawn the gold teeth extracted with a pair of tongs from one of the skulls to pay for the exhumations. A real example of a courageous woman who refused to forget.

Grave number fifteen in the cemetery was occupied by a former British consul, Mr A. S. Lindsay, who had died in 1976 and expressed his wish to be buried there, alongside his compatriots of yesteryear. He wasn’t with the others, in the line next to the back wall, but in the garden itself, next to some hedges. This was also the resting-place of his wife, Mrs Irene Amadiós de Lindsay, who died in 1991 and decided to keep her husband company for all eternity.

There was only one anonymous grave, number one. It was this grave, and its unknown occupant, that really interested me. All my hope was placed on that grave. All of it. This was the chest I had been searching for, and that was where the treasure had to be, the solution to all my problems.

I walked along the front of the cemetery and entered a side path to reach the back. I glanced nervously in all directions. The shutters on the nearby houses were closed. All the neighbours were still asleep. I had nothing to fear and so I calmed down. I picked my way through the brambles and approached the wall at the back. It must have been two metres high and was made of rough stone. I had another look around and took a couple of deep breaths, as if about to go diving. Suddenly, the clatter of a shutter being raised made me quickly retrace my steps. Having arrived back at the entrance, I realized if I climbed the lamp post on the left, it wouldn’t be too difficult to gain access to the enclosure. The post was made of cement and had several cracks in it. Despite the risk of electric shock indicated by the drawing of a lightning bolt, I made up my mind. I glanced up and down the road – there were no cars coming. Then I stuck my foot in the first crack, in the second and the third. I climbed up onto the wall and jumped inside with determination. Although my feet were only separated from the ground for a few tenths of a second, I felt as if I was suspended in mid-air for much longer. And during those moments that seemed to go on forever, I recollected.

This whole adventure had started because of a seemingly unimportant newspaper article – because of that and my customary distrust of human nature. I just couldn’t believe someone would be so generous for almost seventy years. It was impossible, there had to be something else. Some hidden interest. Some reason that explained all that self-denial and open-handedness. Everyone was guilty until proven innocent. Egoism dominated all our lives. This was the energy that moved the universe. And the attitude of that old man flew in the face of my understanding of the human condition. It just couldn’t be unselfishness, I kept saying to myself, there had to be something else. And I was going to find out what it was. Even if it was the last thing I did. I couldn’t allow this gesture of his, repeated over such a long period of time, to shake the foundations of my own convictions. I suppose the fact the events took place in Vilagarcía had something to do with it, I won’t deny it. After all, this was where I had been born and spent most of my childhood.

The itching sensation had got inside my body, and I started ruminating about that blasted story I’d read one morning over breakfast four years earlier. Because the important thing wasn’t what you told, but the way you did it. And in that place, my feet on the gravel in front of that anonymous grave, number one, I was hoping to find the way to do it or at least to unearth an ending to the story that had been pursuing me for so long. And thus to unravel the mystery surrounding the life of Delia Cores and her son, Edelmiro, gardener for the English.

RESIDENT OF CEA RECEIVES BRITISH AWARD

FOR LOOKING AFTER A CEMETERY FOR 70 YEARS

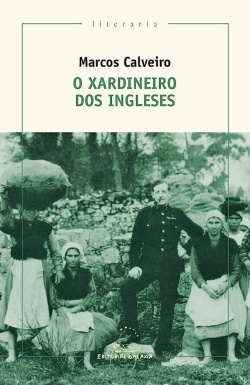

The Defence Attaché of the British Embassy yesterday presented Edelmiro Cores with the medal of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the first to be awarded to someone outside this organization

Staff Reporter. Vilagarcía. Almost seventy years of selfless dedication to the care of the British Naval Cemetery in Vilagarcía on the part of Edelmiro Cores, of the parish of San Martiño de Cea, have been afforded public recognition by the British authorities. The guest of honour received yesterday, in Vilagarcía Town Hall, the medal of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission at the hands of the Defence Attaché of the British Embassy in Madrid, Anthony Peters, the first this organization has awarded since it was founded to someone not on its staff.

Edelmiro Cores had explained to the British Consulate in Vigo a year ago that he could no longer see to the maintenance of the cemetery because of his advanced years, now that he was over ninety. His dedication was officially recognized with an award he received yesterday in an official act in the town hall in Ravella Square. From now onwards, Vilagarcía Town Council will perform this task thanks to an agreement with the authorities of this country, as the mayor, Dolores García Giménez, explained.

The story of Edelmiro Cores’s relationship with the British cemetery has uncertain origins. Whether because of his advanced age or his discretion, he refrained from giving explanations to the journalists who attended the act. When they insisted, Edelmiro replied nervously, ‘I do it because of my mother, Delia; nothing more.’

For decades, he looked after the enclosure until prevented from doing so by the passage of time. Apart from seeing to the garden and the cleaning, he would also open the enclosure whenever someone from the Consulate came on a visit. The last burial to be held there was that of the British consul and his wife.

The recognition of this resident of Cea took place yesterday afternoon in the function room of Vilagarcía Town Hall, with the presence of the guest of honour and his family, the British consul in Vigo, the Defence Attaché of the British Embassy in Madrid – ship’s captain Anthony Peters – and the aforementioned mayor of Vilagarcía. The British diplomat emphasized that this was the first time the Commonwealth War Graves Commission had made this award to someone from outside the organization. Apart from the medal, Edelmiro Cores also received a present from the British Embassy. For her part, the mayor of Vilagarcía gave the Embassy’s representative a book with old postcards of Vilagarcía de Arousa.

AROUSA BAY

I

The barefoot children run about like startled cattle in the streets moistened by the light rain that has been falling since dawn. With pushes and jokes, they tell everybody about the arrival of the English squadron, which has been sighted from Ferrazo Point, on the midday tide.

‘The blullaques! The blullaques!’ they cry in their pidgin Galician English in and out of every corner of Vilagarcía.

Soon, from the elegant quarter of Prosperidade to the popular Peixería Square, passing through the sailors’ district of Castro, everybody knows the good news and quickly starts preparing to welcome the hundreds of sailors and officers who will be keen to wet their whistle and fritter away their pounds and pence.

The tavern owners are busy in their cellars with the barrels of wine, adding raisins and sugar to obtain that genuine Malaga Wine the English like to slurp so much on nights of carousing. In the store El Precio Fijo, Narciso González’s ironmonger’s and Carrete stationer’s, the shop assistants get out their best items and arrange in the shop windows the postcards of the town that sailors buy by the dozen to send to their families in England, or else to sweethearts they have abandoned – pregnant or in love – in every port they have visited. In the Moderno, Universal and Inglés cafés, the waiters get ready for the impending invasion and take down the crockery from the shelves.

Word has it on one of their previous visits more than a thousand bottles of La Cruz del Campo and La Austríaca beer were sold in Poyán café, since it seems the thirst of these sons of Perfidious Albion is infinite. Apparently, on that day, not a drop of alcohol was left in the whole town, or on the dressing tables of ladies, since to calm them down there were scoundrels who went so far as to mix cologne with water as a way of preventing thirsty Saxons in their protests from smashing up the local establishments.

In grocery stores, attendants take stock of the provisions and merchandise they have, since ships need flour, tea, sugar and fruit by the hundredweight for their kitchens and holds. The maids – mucamas and menegildas – who serve in the town’s principal houses get out their best clothes and wait impatiently for their Sunday afternoon off, when they will be able to walk arm in arm in the Alameda or the Mariña under the drizzle, amid a shower of compliments from chivalrous sailors who always raise their caps as they pass, since to them everything at sea represents fish, be it a lady, a servant or a peasant girl.

Fernanda, the madam at the well-known and much-used brothel-house on Vista Alegre Street, as soon as she hears the shouts of the children announcing the news, gets one of her trusted pupils out of bed with pushes and shoves so she can go and send a telegram. The girl, still feeling drowsy, goes out into the street half-dressed and with her hair in a mess, shocking two young ladies with their umbrellas open who are making their way to the Buhigases’ house for a pre-prandial on this damp morning at the end of February 1911. Despite the urgency Fernanda imposed on her, she stops at a tavern near Verdura Square and quickly downs a glass of brandy before taking to her heels. The tavern owner demands the price of the drink, so the girl comes slinking back in, leans over the counter and, depositing her large breasts on top of it, gives the astonished owner a resounding kiss on the cheek.

‘There’s your tip, you know where you can get the rest, you imp!’ she cries before disappearing through the door once more, while the clients at the different tables laugh their heads off at the shameless hussy’s wit.

Having raced along Calderón Street, keeping close to the houses so she doesn’t get too wet, she finally reaches Santa Lucía Square and takes her stand in front of the telephone exchange. Before going in, she looks up, discovers all those cables and metal posts on the roof of the building and crosses herself three times in succession, as if she has just bumped into a soul on its way to purgatory. She doesn’t understand very much about all those strange trinkets that are meant to signify progress, but seem to have more to do with the devil than with our Lord, since she is a great believer, especially in St Benedict of Lérez. She can’t work out how you can speak down those receivers, without even having to shout, to someone who might be in Pontevedra, or much further away, in Buenos Aires, and how your voice can traverse all that rough sea in between, since she has a cousin who emigrated and it takes two weeks to make the crossing. What she does like, however, is all the public lighting, it’s a pleasure to wander down the streets at night beneath the yellowish glow of street lamps rather than in the pitch darkness of her childhood, out of which a boar, a wolf or any other kind of pest might suddenly appear. Not to mention the cars, their glistening bodywork and leather seats… albeit she’s never actually been in one. All she did was catch the bus that goes to Cambados a couple of times, what with the rumbling of the engine and the rain drumming on the windows. It was a wonderful journey, though with all those potholes on the road it felt more like a boat traversing the estuary to Pobra do Caramiñal on a day with a north-easterly wind.

Inside the telephone exchange, from two wooden cabins on the right come the voices of people who don’t realize there’s no need to shout when speaking into those Bakelite phones.

‘Manuel, Manuel, is that you?’ yells a desperate woman inside one of them, as if she thought the man was somehow stuck inside the apparatus.

The girl smiles on hearing the poor woman. She’s a little wet from the rain, but doesn’t feel cold, the wake of the complimentary liquor burning inside her chest. Wringing the water out of her hair with her hands, she goes up to the counter, where there is a telegrapher, who gazes at her with petrified eyes beneath his peaked cap. She vaguely seems to recognize him, he might have paid a visit to her boudoir, but thinks it better not to ask; in her profession, discretion is more important than a pair of shapely hips, Fernanda always says. The telegram she has to send is addressed to a madam in Santiago. The text is brief and to the point, and the telegrapher can’t help smirking when he hears it from the girl’s thick lips: ‘Squadron in port. Stop. Send plenty of cattle. Stop. Big and busty.’

The girl gives a couple of coins to the telegrapher, who carries on smiling, goes out into the street, where it’s almost stopped raining, and leaves the poor desperate woman inside the cabin.

‘Can you hear me, Manuel, can you hear me!’

Before returning to Fernanda’s, she decides to head down to the quay to see some of the ships, which under the command of Admiral Sir William H. May have started dropping anchor in the waters of the bay. On the way there, she bumps into Tonecho, the local lunatic, who has also set out in a carefree mood to meet the English. The girl realizes the poor man is barefoot, despite the cold and the puddles. Some lowlifes must have made fun of him again and stolen his shoes. Tonecho earns a few coins by working as an errand-boy at the station, in some store or at the quay. Unluckily for him, he’s also the laughing stock of lots of young men in Vilagarcía, who invite him to a wine or a cigarette just so they can crack jokes at his expense and abuse him. The girl remembers when he was a boy, wandering the streets; as far as she knows, he doesn’t have any family, except for the odd charitable soul who gives him something to eat or some old clothing. He doesn’t have a house of his own and usually sleeps in one of the sheds where the fishermen keep their tackle in the district of Castro.

In the Mariña, there is a huddle of people; even the sky has called a truce and decided not to put a dampener on the squadron’s arrival. It has cleared, and a few timid rays have pierced the storm clouds, tearing the sky into ashen streamers.

‘The Germans are coming too!’ exclaims one old woman.

‘What was that?’ asks Fernanda’s pupil eagerly, having missed the old woman’s comment.

‘It seems a German squadron has also entered the bay,’ explains a man beside her.

The girl cannot believe her ears and quickly sets out to inform the madam. Fernanda’s going to have a heart attack when she hears about the Germans’ arrival. They’re better customers than the English, red-haired satyrs with extravagant tastes. The girl knows all about that from their previous visits. After all, she’s a decent girl herself and there are certain things she won’t do, however many marks one of those lewd Teutons with their devilish looks might be offering.

Don Valeriano Deza, the mayor, and the British vice-consul, Mr Cameron-Walker, stride arm in arm through the huddle of people in order to welcome an English tender approaching Ferro Quay.

‘Make way for the authorities!’ shouts the policeman walking in front of them, shoving aside anyone who doesn’t pay attention.

Delia Cores, a pretty blue-eyed young woman from Rubiáns, is one of the first to fall to the ground because of that brute of an officer. Today was the first time she came down to Verdura Square on her own, carrying a basket brimful of cabbages on her head. Early that morning, her mother wasn’t feeling well and her father shouted at her, accusing her of being a slugabed. Delia, to prevent the argument getting worse, offered to take her place.

‘I can go, father.’

‘Will you manage to do the sums?’ he spat.

‘I know what has to be done, I’ve been with mother lots of times,’ replied Delia.

‘Yes, but…’ her mother started saying from her bed.

‘You, be quiet!’ shouted her father.

‘I can do it, father.’

‘I think the girl’s…’ Delia’s mother intervened again.

‘Sort it out between yourselves. I’m going to the fields, but at lunchtime I want to see the money. You’ve been warned!’ growled her father in a threatening tone.

Delia knew her father’s threats were not in vain, but were always carried out, and so that is why she is there now, on her knees in the Alameda mud. In amongst all the legs, skirts and feet, she tries to find the few coins she received from the sale of cabbages, which fell out of her apron when the guard pushed her over. She thinks she’s got them all when she discovers a 10-cent coin glinting next to a man’s clogs. She heads towards it, but suddenly a hand appears and sweeps it up.

‘Hey, that’s mine!’ she shouts in despair, jumping up and grabbing the petty thief’s hand.

Tonecho writhes like a beast, and Delia can hardly keep a hold of him.

‘Open your hand! I don’t want to hurt you!’ she cries.

All around, men and women’s feet keep stamping on them like horses’ hooves. Delia can’t take any more and lets go of her prey in such a way that Tonecho gets bumped on the head and opens his hand as a result of the blow.

‘Hey, what are you doing down there?’ shouts a man above them.

The 10-cent coin rolls along the ground, and Delia finally lays hold of it before it disappears into a puddle. She quickly gets to her feet and moves away from all the kerfuffle. She thinks she has everything. Next time, she had better go straight home and stop messing around, as her mother warned her before she set out. But today, after selling all the products in her basket, curiosity won out and she decided to head down to the quay. She had never had the chance to see the English everybody talked about coming into port. That was my mistake and I mustn’t repeat it, she ponders.

Suddenly, Delia has this strange sensation. As if somebody were spying on her from behind. She turns around and finds the culprit. Tonecho is staring right at her. The blood is gushing from his forehead and pouring down his cheek. Delia cannot resist his suppliant look. Without thinking, she sticks her hand in her apron, gets out the coin and tosses it towards him. Tonecho catches it in the air and smiles. He then races off like a firework, jumping in all the puddles with his bare feet. Delia is aware she’s just done something stupid and thinks about her father’s threat. She doesn’t know what to do, but she can’t go home like this. Caked in mud and ten cents short. If she does, her father’s threats will become real.

In concern, she returns to Verdura Square to collect her basket. All the saleswomen have gone; there is a bunch of damaged goods scattered on the ground. She gathers what doesn’t look so bad, puts it in her basket and looks for a corner of Comercio Street to sell it and try to get back the coin she’s lost. The hours drag by, and Delia, sitting next to her basket, watches people pass without paying any attention to her or to her cabbages. In despair, her hand in her apron pocket, she keeps jingling the coins, counting them over and over and thinking perhaps her father won’t miss ten cents.

‘Hey, move along, you can’t stay here!’ shouts a guard, suddenly turning the corner.

She recognizes him at once. She is in no doubt. It’s the brute who pushed her over on the quay that morning. It’s because of him that her coins fell out and she ended up giving Tonecho the 10-cent coin. Fury filling her nascent breasts, she turns on him and answers back.

‘You’re the reason I’m here!’

‘What’s that you’re saying? Don’t make me wallop you!’

‘Give me back my coin.’

Enraged, the guard comes striding over and knocks over her basket, spilling all the cabbages. Owing to the ruckus, some passers-by stop and form a circle to see what is going on.

‘I told you to move along!’ he shouts again, grabbing her by the arm and lifting her roughly off the ground.

‘I’m not doing anything wrong!’

The guard, who is beside himself, raises his hand to beat her, but at that precise moment somebody stops him by grabbing his arm. It’s an English sailor in his elegant blue jacket with the shiny gold buttons.

‘Sorry,’ apologizes the sailor with a smile, to the surprise of the assembled company.

‘What the hell are you doing, Englishman?’ complains the guard, letting go of Delia in the face of this new prey.

‘She’s only a girl!’ replies the Englishman, releasing his arm.

‘Mind your own business, Englishman!’ says the guard, turning to confront him.

The bluejacket adopts a dumb expression and smiles again as if he didn’t understand the gravity of the situation. The guard hesitates, uncertain how to proceed. Delia uses these moments of doubt to make a dash for it, but another guard appears out of the crowd and snares her like a little animal.

‘Where do you think you’re going, you scamp!’ he hisses.

Encouraged by the presence of his colleague, the first guard takes heart.

‘So, what you going to do about that, little Englishman?’

The bluejacket gives him a shove and knocks him to the ground. The people move aside in fear. The other guard lets go of Delia and goes after the Englishman.

‘Careful!’ shouts Delia to warn him.

The Englishman is slow to react and, when he does, the guard falls on top of him. From among the crowd appears another sailor who moves Delia out of the way and gets involved in the fight. She discovers he’s not wearing the same uniform as the Englishman, but is dressed all in white with a black jacket and a peaked cap with red locks poking out. He’s short, but as strong as an ox. The uproar is tremendous, the guards and sailors throwing punches left, right and centre. A loud whistle is heard at one end of the street, and people make way as two guards rush onto the scene. The sailors quickly start running in the direction of Bilbao Street, the Englishman grabbing Delia by the hand and dragging her along with them in their crazy escape. All the guards go running after them.

‘This way!’ Delia suggests to her two saviours as they enter Ravella Square.

The two sailors follow her, and the three of them hide in a covered wagon full of boxes in front of the Varietés theatre. The guards pass by without stopping, rushing in the direction of the town hall.

‘James,’ says the bluejacket, holding out his hand to his fellow fighter.

‘Fritz,’ replies the other, giving it a firm shake.

‘Stop wittering, you two, and let’s get out of here,’ murmurs Delia with unexpected daring, and the three of them head along Cervantes Street towards Rubiáns.

Delia walks silently, and the two sailors follow on behind. When they reach the edge of the town, where the houses are replaced by fields, Delia takes her leave.

‘Thank you very much, I have to go now,’ she explains in Galician, unsure whether these two clowns can understand a word she’s saying.

They smile at her and remain quiet. Delia starts walking, but still they follow obediently behind her.

‘Go away!’ she shouts, turning around.

All she needs now is to arrive home without the 10-cent coin and with these two blowflies in tow, she thinks. She starts walking again, and they follow her like dogs.

‘What is it with you?’ she stops.

‘What’s your name?’ asks the bluejacket.

‘Get away with you!’

The two of them stand dumbly in front of her and don’t move.

‘Let’s see if you can understand this!’ she yells, grabbing hold of some stones from the ground and hurling them at the sailors.

They laugh and easily dodge the stones. Delia laughs as well when she sees them leaping about and pushing each other. Two water carriers pass by with their buckets on their heads. Delia knows them by sight and decides to stop playing around – she doesn’t want them telling her parents – and to join them.

‘Goodbye, my lady!’ cries the bluejacket from a distance.

‘Until next time!’ shouts the other sailor.

The water carriers look at her, and she smiles in surprise. Those two layabouts were making fun of her, they knew perfectly well what she was saying. Delia is missing the coin and has spent the whole day away from home, but she quickens her pace in a contented mood, not caring what her father might say or do. She turns her head and sees the two sailors walking down the road, arm in arm. Those two rogues have brightened up her day and given her life.

Later that night, James and Fritz stagger out of a tavern in Castro, having celebrated their victory over the guards with a succession of beers and bowls of wine. The sound of a siren warns them that the last tenders going back to their ships are about to depart. Swaying from side to side, they run as fast as their bingeing will allow them. In the Mariña, they coincide with Tonecho, who is straining at a wheelbarrow containing two sailors whom alcohol has vanquished.

The two friends take their leave of one another on Ferro Quay with a sentimental, drunken embrace.

‘Goodbye, my friend!’

‘Auf Wiedersehen!’

James jumps into the launch with the Cross of St George on its pennant, while Fritz jumps into the one with a black eagle. Tonecho arrives with his cargo, panting heavily; the sailors keeping watch on the quay lift the drunk men up and throw them onto the English boat as if they were a couple of sacks of potatoes.

Tonecho lights a cigarette an Englishman has given him and watches the two vessels leave the quay. For a few moments, the tenders move alongside one another, as if egging each other on, until one turns to port and the other turns to starboard, heading towards their respective ships.

A slippery moon appears in the dark sky, making the estuary and Tonecho’s toothless gums glisten with its silvery reflection. In the distance, the night breeze carries the muffled sound of a tavern song that is just finishing. Vilagarcía finally falls silent until the next day, when the English and the Germans will invade it again.

II

The locomotive Río Umia belonging to the West Galicia Railway Company – or the Tebés as the Trulocks’ company is known to the people of Arousa – pulls various carriages along, which early on Sunday morning at Carril Station deposit hundreds of Santiago students who have come to see the English and German squadrons anchored in the bay. The young men, like mercenaries in search of well-earned booty, amble along Martínez Avenue and pass through the district of Prosperidade, where some of them linger, dishing out compliments and whistles to the maids shaking carpets, clothes and feather dusters from the balconies of local potentates’ villas. Finally, the racket reaches Ramal and heads through the Mariña towards the tree-lined Alameda.

Self-respecting people have yet to come out of Mass and, on the Alameda bandstand, the musicians of the municipal band tune their instruments and arrange their scores for the concert. Only Tonecho, with an extinguished butt hanging from his lips, approaches the university students and welcomes them with grand gestures and guffaws to see if he can cadge a bowl of wine or a cigarette. The students disperse down different streets, some searching for taverns and brothels, others staying behind to make fun of poor Tonecho, and still others heading for Ferro Quay to contemplate the ships and the first tenders bringing English and German sailors in the mood for having fun on this pleasant Day of the Lord.

At midday, at the end of the service, the bells of the parish church toll the faithful out of church. Out in the open, gentlemen in suits, waistcoats and hats light their fragrant cigars and start chatting to one another, while their suitably attired wives head for the cake shops to order meringues and sweets for after lunch. On their return, the men put out their cigars, offer their arms and, with the children swarming about like bees, head for the Alameda to see, be seen and listen to the concert of the municipal band on the bandstand. Their marriageable daughters gossip nervously because, after waiting impatiently for a week, they are about to see their suitors again in the distance, beneath their mothers’ disapproving looks.

At once, the Alameda, the whole Mariña and Comercio Street fill with people, and you can barely take two paces without bumping into someone. In Narciso González’s ironmonger’s, the queue of sailors waiting to buy postcards of the town reaches all the way to Calderón Street. Some of them while away the time wooing the girls that pass by, competing in compliments and clever turns of phrase with the lads from Compostela. Even Delia has to put up with their verbal assaults and push her way through that crowd of ladykillers and Casanovas. She is late for her meeting with James and Fritz.

In recent days, they have met up often, despite the initial opposition of Delia’s parents when she innocently told them all about it. The old man snorted, but when his daughter placed the money from the sale of cabbages into his calloused hand he calmed down like a dog that has received a bone from its master. Despite the fact she kept a few coins back to buy medicines for her mother, who wasn’t getting any better. Delia had decided she couldn’t live in fear. The slap her father had given her the day she returned home from the market without the 10-cent coin had been a landmark. Things had to change. Besides, being with James and Fritz made her feel like another woman, stronger, different. The company of those two foreign sailors had revealed another life to her, had opened her eyes in a way that had never happened before. She had been blind up until that moment and hadn’t known or even suspected this.

They came across her by chance the day after the fight with the guards, touting cabbages once more in Verdura Square. Delia had had a terrible morning and the basket at her feet was still full of produce when those two rogues, smartly dressed now, appeared before her.

‘Haven’t the guards arrested you yet?’ she asked with a brazenness she didn’t realize she possessed.

They looked at her in surprise and shrugged their shoulders. As if they didn’t comprehend.

‘Don’t act all dumb, I know you can understand me,’ she insisted.

James and Fritz stared at one another and guffawed loudly. Delia felt awkward because she thought they were laughing at her.

‘She’s a funny girl,’ remarked James.

‘Ja, ja,’ confirmed Fritz.

‘You’re a couple of clowns! Clear off, you’re frightening away the customers!’ she shouted angrily, not understanding a word.

‘How much?’ asked James.

‘You what? Why can’t you talk normal?’ exclaimed Delia, who was getting more and more frustrated at their jokes.

James stuck his hand in his pocket and pulled out some coins.

‘I suppose you can understand this,’ he said in heavily accented Galician.

Delia felt a little ashamed of her attitude and fell silent with her eyes on the ground.

‘If we buy everything… will you walk with us…?’ asked Fritz with a certain amount of difficulty.

Delia smiled. They’re certainly a pair of layabouts, she thought, but she liked them and had nothing to lose, since there was nothing she owned, not even that thing society ladies called ‘reputation’, a young lady’s most prized possession, as they liked to declare.

‘Just a walk, right?’ she said, scooping up the coins in James’s palm and stuffing them in her apron.

Fritz took the basket, and the three of them started walking across Verdura Square beneath the astonished looks and malicious smiles of the other saleswomen. Delia didn’t care what they thought, her pocket was full, and there was no harm in going for a walk with these two before heading back to Rubiáns. She could look after herself.

Over the following days, James and Fritz returned to the square and bought all her merchandise. They told her they had docked at Vilagarcía about half a dozen times before and, having spent several months there, drinking and chasing girls, they had picked up a smattering of Galician. About Fernanda’s young women, who were supremely adept in the art of tongues and other corporal studies, they kept quiet. Delia grew to trust them, they were nothing like the rough young men in Rubiáns, and one day, before returning home, she agreed to walk a little further with them to show them some of the most picturesque places in the town and surrounding areas. They knew them perfectly well, but insisted she take them to see them once more.

‘It’s not the same seeing things through your beautiful eyes,’ James had remarked flatteringly.

Delia led them to the district of Castro, they walked along the beach in Vista Alegre, next to the large house, and reached Comboa Cove, in Vilaboa, where they admired the impressive mansions and carefully tended gardens of the Dukes of Terranova, Señor Calderón and the González Garra family. She also showed them the magnificent wooden building of the La Concha de Arosa spa, which was empty and forlorn, since the bathing season, which ran from June to October, hadn’t started yet.

‘There is no better hydrotherapeutic installation in all the country,’ explained Delia proudly.

At her remark, James and Fritz glanced at each other in confusion, as they always did when they hadn’t understood some word or expression.

‘What was that?’ asked James.

‘What?’ she replied.

‘Hydro… tetic… installation…’ stammered Fritz.

Delia went all red because, truth be told, she didn’t know. She had just repeated a phrase she’d heard one elegant young lady gabble to another one day in Comercio Street.

‘What an ignorant pair you are!’ she exclaimed, attempting to avoid the subject and setting off again.

Delia had got to know them a bit by now. James was the more talkative, but also the bigger liar and the more dangerous. He was very handsome and had this movie star or vaudeville actor’s moustache. Fritz spoke less, but didn’t miss a jot of what was going around him with his deep blue eyes. Sometimes, she would find him staring at her in amazement and feel a little embarrassed. She thought rather than a question of character, which might also be the case, it was really because James was much more proficient in the language. Fritz sometimes looked lost, as if he couldn’t understand much of what was being said. Of one thing, there could be no doubt – they both enjoyed their beers, wines and fights in equal measure.

She liked a lot to hear them talk about their countries, people, customs and places. And she was always mesmerized by the things they told her, especially James.

‘You must be kidding,’ Delia had reproached him.

‘No, woman, I’m not,’ James had replied vehemently.

‘I don’t believe you!’

‘Well, that’s your problem.’

‘What do you think, Fritz?’ she asked.

The taciturn German did not reply, but shrugged his shoulders in a gesture he repeated at all hours. James insisted on the truth of his story, and Delia carried on not believing a word of that business about the women. He had said, in England, lots of women were protesting in the streets, demanding the vote and other rights they had been denied because of their condition. Some had even been arrested by the police during protests and had defended themselves with kicks and thrusts with their umbrellas when the officers took them captive. The way things were going, and in spite of the large amount of opposition, it wouldn’t be long before they achieved what they wanted. Those English women were something!

‘Women get the vote, what nonsense!’ Delia had exclaimed, pushing James because of what she took to be a joke.

The month of March was warmer than anyone could remember, and the three of them wandered along the beach in Vista Alegre, which was without any bathers, since they normally arrived after midday, when the sun was at its hottest. At that hour, the beach would be transformed into a bustle of children jumping about in the water with toy yachts, maids looking after babies under awnings, young men making human castles on the sand, young ladies walking along the shore and wetting their feet beneath embroidered parasols.

James made it look much worse than it was and fell flat on the beach because of Delia’s gentle shove.

‘You’d better watch out!’ he warned her, standing up and brushing the sand off his uniform.

Fritz, who had gone over to the shore to gather some shells for his collection, came to Delia’s defence and threw himself on top of James, the two of them falling to the ground.

‘You pair of clowns!’ cried Delia as they mock-fought each other.

The two of them abandoned their pretend struggle and stood up. They gave her a malevolent look and grinned mischievously at each other.

‘Don’t even think about doing anything to me, you hear?’ Delia warned them, trying unsuccessfully to adopt a serious expression.

James and Fritz went towards her, step by step, with the intention of capturing her. Delia took a few steps back and then started running along the beach as fast as she could.

‘Stay there! Leave me alone!’ she shouted as she moved away.

They laughed out loud as they chased her. It was like two cats pursuing an unfortunate mouse. Delia laughed as well and tried not to lose sight of them, which meant she didn’t realize how close she was to the water.

‘Look what you’ve gone and done!’ she shrieked, really annoyed this time, with the water up to her ankles. ‘These are the only shoes I have! And they’re going to get spoiled!’

They didn’t pay her any attention, but lifted her by the arms and strode with her back to the town. Delia couldn’t understand what it was they wanted, but had no other choice than to let herself be carried along.

When not far from her parents’ house she stopped to change her shoes, Delia couldn’t help admiring them. Her feet ached, but see how pretty they were! She had almost fallen over on several occasions, but they really were wonderful. The heels, the golden buckles, the soft black leather. Accompanied by Fritz and James, one on either side, walking on them in the direction of Rubiáns, she felt like one of those cabaret singers or dancers that are said to perform on stage in the Varietés theatre. But no sooner had she put her feet back in the old sodden shoes than her vaudeville performer’s dreams evaporated as if by magic.

‘What is it?’ asked James when he noticed her displeasure.

‘Nothing,’ she replied sullenly.

Delia had decided to live her life, and her father, so long as she brought him the money from the sale of cabbages, left her in peace, but she knew perfectly well there was no way she could wear those new shoes into the house.

‘I can’t wear them, my father would kill me,’ she said, handing them back to James.

He wasn’t sure what to do and looked at Fritz, who shrugged his shoulders as normal.

‘Go on then, put them back in the box,’ Delia said to James.

Neither he nor Fritz could understand a thing. They couldn’t comprehend what was wrong with a pair of shoes. She had looked so happy, so radiant, when she had them on. Even though she had refused to enter the store Simeón after their race from the beach. It was James who had taken off one of her wet shoes while she stood protesting in the street. At the counter, the shop assistant couldn’t believe the sight that met his eyes: two sailors, one English, one German, with a dripping wet shoe. It took them a while to agree on a pair from all the ones he showed them. In the end, it was the shop assistant who decided for them. With the handwritten note he gave them and the box with the shoes, they paid the cashier between them. Out in the street, content with their excellent purchase, they couldn’t find Delia anywhere. In concern, they searched the surroundings until they eventually discovered her on a bench in the Ravella gardens, sobbing.

‘You humiliated me!’ she exclaimed unhappily as they approached.

Fritz and James glanced at each other, uncertain what was going on. All they had wanted was to rectify their mistake on the beach.

‘Leaving me like that, missing one shoe, in the middle of Calderón Street. Everybody kept looking at me!’

‘We only…’ began James.

‘You’re a pair of wretches! Having a good laugh at the expense of a poor peasant woman!’

At this point, Delia began to appreciate how comic the situation was – the two of them standing there, looking sheepish, Fritz holding a sodden shoe and James a box.

‘What have you got there?’ she asked with curiosity, sniffing loudly.

James didn’t reply, but pulled back the lid and held out the box so she could see the contents. Delia’s face lit up as if an early, verdant spring had suddenly exploded right on top of them, in the branches of the lush magnolia overhead.

Delia carries on dodging the students that get in her way and finds James and Fritz next to the Alameda bandstand. The musicians are putting away their instruments, and the sailors are chatting to them. Delia feels she can’t breathe among so many people and thinks she won’t ever be able to reach them.

Text © Marcos Calveiro

Translation © Jonathan Dunne

Other books by Marcos Calveiro are available to read in English – see the page “YA Novels”.